Here it is, folks, the final product.

It is a beast. One famous blogger said of it, “This post is so big, you can see it from space.”

We hope you take the time to give it a thorough read. We think it important and will soon be at the center of the market’s radar.

Summary

- Our analysis provides kind of a Grand Unified Theory (GUT) of what is currently taking place in global financial markets

- The massive borrowing by the U.S. Treasury is crowding out emerging market capital flows

- The structural factors that have kept long-term interest rates low and term premia repressed are fading

- The U.S. budget deficit is exploding

- The Treasury has to increase its market borrowing as the Fed rolls off its SOMA Treasury portfolio

- Social security has moved into deficit and borrowing from its trust funds to finance the on-budget deficits is over

- Globalization is under threat, and foreign capital flows into the U.S., particularly the Treasury market, are declining

- The yield curve is flat for technical reasons, and we believe term premia will increase

- We expect a measured move in the 10-year Treasury yield to 4.25 to 4.40 percent, much sooner than the Street anticipates

- Crowding out in the emerging markets will continue

“Reagan proved deficits don’t matter.” – Dick Cheney

Memo to Dick Cheney:

- Deficits and the public debt are starting to matter. Really.

- It is now more strikingly true than ever given the U.S. public debt-to-GDP is more than 3.4x higher than when President Reagan took office.

Emerging Market Debacle

Go no further than the debacle currently taking place in the emerging markets (EM), which began in the second quarter of this year, to witness the consequences of the U.S. Treasury’s trillion-dollar-plus demand shock for global funding.

In a closed financial system and a non-QE world, price (interest rates) would adjust to move the capital and debt markets back to a more sustainable equilibrium. The rise in interest rates would force the government to borrow less as higher interest rates crowd out other spending. Also, the supply of loanable funds to the government would rise as savings increase.

That is not the world we now inhabit, however, where global financial repression by central banks has resulted in a “rent control” like shortage of dollar funding. The shortfall is now being plugged, in part, by the residual capital flows, which had been chasing yield in the emerging markets over the past several years.

That is the sucking sound you have heard since late April.

Crowding Out Begins

Therefore, it is no surprise, at least to us, global markets, beginning with the most vulnerable twin deficit EMs, are experiencing significant pressure from the crowding out caused by the U.S. Treasury’s massive increase in market borrowing.

U.S. Government Hoovering Up Global Funding

The following table illustrates the Treasury borrowed close to $1 trillion from the public in the first eight months of 2018, more than a trillion dollar swing from the same period last year.

Almost 85 percent of the 2018 new debt issuance was in the form of marketable securities, that is borrowing from the public markets, of which more than half was T-Bill issuance, explaining the pressure on short-end of the curve and a growing scarcity of dollars.

Debt Ceiling And Treasury Borrowing In 2017

Because of the constraints on raising the debt ceiling in 2017, total net Treasury issuance to the public from January and August 2017 was net negative. Marketable note and bond issuance did increase around $200 billion, however, probably over worries about disrupting the market and liquidity concerns.

The government was financed in January to September 2017, primarily by the Treasury reducing its cash balances at the Fed and “other means of financing,” such as deferring payments to federal retirement accounts, and a game of three-card monte by shifting funds around.

Means of Financing

Ways in which a budget deficit is financed or a budget surplus is used. A budget deficit may be financed by the Department of the Treasury (Treasury) (or agency) borrowing, by reducing Treasury cash balances, by the sale of gold, by seigniorage, by net cash flows resulting from transactions in credit financing accounts, by allowing certain unpaid liabilities to increase, or by other similar transactions. It is customary to separate total means of financing into “change in debt held by the public” (the government’s debt, which is the primary means of financing) and “other means of financing” (seigniorage, change in cash balances, transactions of credit financing accounts, etc.). – GAO

The spike in new debt issuance in 2018 is not only caused by the financing of a larger budget deficit due to the tax cuts and big ramp in spending, but also the rebuilding and maintaining of the Treasury’s cash balance at the Fed, and the likely reduction in obligations incurred through “other means of financing” in 2017.

Quantitative Tightening (QT) And Roll-Off Of Maturing Treasuries

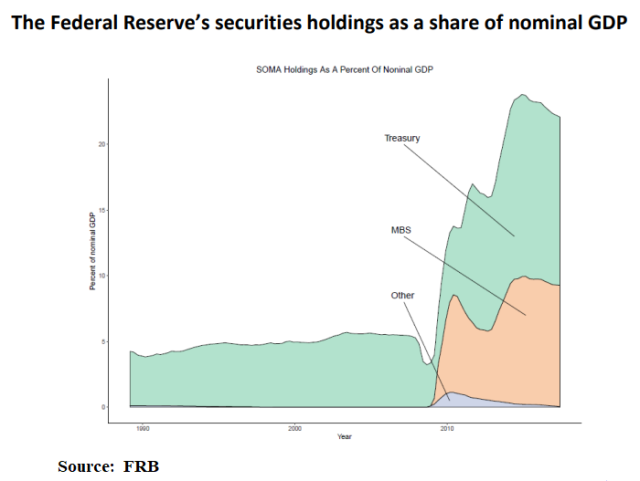

Furthermore, the Fed began quantitative tightening last October, starting its roll-off of the $4 trillion-plus maturing securities (SOMA) purchased during quantitative easing.

Thus far, the Fed’s SOMA portfolio consisting of both Treasury and Agency Mortgage-Backed securities has declined by around $231 billion, which is not insignificant, and equivalent to 6 percent of the U.S. monetary base.

The Fed’s roll-off of $145 billion in Treasury securities in the first eight months of 2018 is a hole that had to be plugged by the market, otherwise the Treasury’s cash balances (checking account) held at the Fed would have declined. The Treasury cash reduction at the Fed is the liability side of the Fed’s shrinking balance sheet , which was not the case during QE where asset purchases created a corresponding liability in the form an increase in bank reserves held at the Fed.

“Global Liquidity”

Global liquidity, in the form of base money is shrinking, but the monetary aggregates continue to grow, albeit slowly, which reflects credit is still expanding, and the continued creation of endogenous money.

The term “global liquidity” is not easily defined, it is an elusive and ambiguous concept, and almost impossible to measure. We believe our analysis and work provides a much clearer framework and more concise picture of the current global market dynamics.

Emerging Markets – The Indicator Species Of Changing Financial Ecosystem

Nevertheless, we are always looking for indicator species of a changing global monetary ecosystem, and the emerging markets and commodities are the best we have discovered.

“Sleeping With An Elephant”

Justin‘s father, the former Canadian Prime Minister and, more important, husband of Margaret Trudeau, once said of living in a world with the United States,

Living next to you is in some ways is like sleeping with an elephant. No matter how friendly and even-tempered is the beast if I can call it that, one is affected by every twitch and grunt. — Pierre Trudeau.

Due to the relatively large size of the U.S. economy, just a small change in its funding requirements have outsize effects on the global financial system. The table below illustrates this point. It’s obese proportion relative to the global economy also makes the U.S. government a price maker in the global financial markets.

The issuance of marketable Treasury securities and the SOMA Treasury roll-off totaled $1.02 trillion in the first eight months of 2018. That is almost four times the sum of the ten largest 2018 estimated current account deficits in the emerging markets; 2.4 times the combined current account deficits of all emerging markets; 3.7 percent of the emerging market 2018 GDP, and almost 5 percent of the GDP of all emerging markets x/ China. Yuuge!

We cannot impress enough what a significant shock to the financial markets this has been in 2018. The Treasury net take-out from the public was net-zero from January to August 2017. Compare this to the first eight months of 2018, in which the U.S. G hoovered up over a trillion dollars from the markets.

In the world of full-blown quantitative easing, where central banks were printing reserves to purchase government bonds (among other assets) the effects were trivial, null, nonexistent.

What about now, you ask? The times they are a-changin’.

Source: Zero Hedge

Countries caught running large deficits are now having their Wile E. Coyote moment.

Why Haven’t U.S. Long-Term Interest Rates Spiked?

Good question.

Real long-term interest rates continue to hover around zero percent, which seems absurd to us, given nominal GDP growth is running at over 6 percent.

Prior to the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) the effective real interest rate on the 10-year Treasury note, measured with CPI inflation, average 2.71 percent from 1962-2008 compared to 0.85 percent during the last ten years, 2008-2018. We estimate the real rate at 0.16 percent at the end of August.

The Bond Vigilante Model suggests that the 10-year Treasury bond yield tends to trade around the growth rate in nominal GDP on a y/y basis. It has been trading consistently below nominal GDP growth since mid-2010. The current spread is among the widest since then, with nominal GDP growing 5.4% while the bond yield is around 3.00%. – Ed Yardeni, August 2nd

Several structural factors have been distorting a “more correct” equilibrium long-term risk-free interest rate — if one exists at all — which are now beginning to fade.

We counsel patience. The train has left the station. Interest rates are on the move.

Fundamentals

Before moving to the fading structural factors, which have held down long-term interest rates, let’s briefly take a look at the fundamental arguments for the collapse of term premia, the flat yield curve, and the low long rates.

1, Lower inflation for longer and forever. The recency bias of almost 30 years of disinflation is a hard habit to break. Cleary, this is an example of adaptive expectations, contradicting how I was trained as an economist in the school of rational expectations, which I never fully bought into, by the way. The disinflationary expectations ingrained in the market is the complete opposite of the problem of former Fed Chairman, Paul Volcker, inherited when he took over an economy in an inflationary spiral. Mr. Volker had to break the back of inflationary expectations with protracted and extremely tight monetary policy, which took short-term interest rates over 20 percent.

The Fed also learned that to be effective, it must have the confidence of the markets and the public. During the 1960s and early 1970s, various Fed chairmen made rumblings about fighting inflation, but they always backed down when the complaints about the resulting higher cost of credit grew loud. Fed Chairman William McChesney Martin, for example, was no match for President Lyndon Johnson, who depended on cheap credit to finance the Vietnam War and his Great Society. Because the markets observed the Fed’s lack of fortitude, they had no expectations that the Fed would conquer inflation. It is extremely costly to bring inflation down if inflation expectations don’t come down. Not until Volcker showed that the Fed could take the heat did the markets believe that the Fed was serious this time. – William Poole, St. Louis Fed

2. The New Economy. The new economy as we have described is more dependent on asset markets than almost anytime in the nation’s history. The fear of a bear market or big market hiccup sends the deflationistas into a tizzy. Even the term “deflation” seems to have morphed into a definition more closely associated with asset price declines than rising consumer prices. Economic progress appears now to be driven by this deflation/inflation dialectic. We concede this argument does deserve considerable merit.

.…the whole inflation/deflation debate has morphed into a dialectic, which is path dependent on asset prices. Stocks values move up to a critical level (which holders likely believe to be permanent) that stirs the animal spirits and kicks economic growth into gear. Inflation eventually becomes an issue moving interest rates higher. The asset bubble pops, stock values go down, confidence declines, aggregate demand softens and deflation now becomes the headline issue. Wash, rinse, repeat. – GMM

3, Negative and near-zero rates in Japan and Europe. A 10-year German bund yield of near 50 bps and a JGB yield of 13 bps are probably the strongest fundamental reason anchoring U.S. rates and holding back yields from spiking, in our opinion. Labeling the interest rates differentials as “fundamental” make us feel uncomfortable as we believe it is more of a technical issue. Nonetheless, even these rates are beginning to move higher. By this time next year, we fully expect that the European bond market bubble to have fully popped.

We reject the thesis global bond yields, including the U.S 10-year note, are driven by fundamentals. Measuring inflationary expectations based on interest rates, which are thoroughly distorted by the technicals of QE, is a fundamentally flawed proposition. The economic signals from the bond markets have been rendered null and void by the central banks.

That may be changing, however.

‘Nuff said. Let’s move on.

Structural Factors

We now examine four changing structural factors that have created a favorable technical environment for the U.S. bond markets, which have kept long-term interest rates abnormally low and pancaked the yield curve:

- The ballooning of the budget deficit during economic expansion;

- QE and its diminishing legacy of reinvesting maturing notes and bonds;

- Borrowing from the social security trust funds,

- Globalization

Budget Deficits

All of Washington, including even Tea Party fiscal conservatives, appear to have abandoned any semblance of fiscal discipline.

The U.S. budget deficit widened to $898 billion in the 11 months through August, exceeding the Congressional Budget Office’s forecast for the first full fiscal year under the Trump presidency.

The budget deficit rose by a third in the October to August period from $674 billion in the same timeframe a year earlier, the Treasury Department said in a statement on Thursday.

The U.S. fiscal gap has continued to balloon under President Donald Trump, raising concerns the country’s debt load, now at $21.5 trillion, is growing out of control. A combination of Republican tax cuts enacted this year — that will add up to about $1.5 trillion over a decade — and increased government spending are adding to budget strains. – Bloomberg, Sept 13th

The following table is an estimate of the Treasury’s financing needs over the next five years. We don’t put much faith in the precision of long-term economic projections. Politics can change, and policies will change. The economic situation could also go sideways causing a crisis.

They do, however, provide a framework, a basis for analysis, and usually get the direction and zip code correct.

What is clear, however, the Treasury will tap the markets for its trillion-dollar-plus funding needs for as far as the eye can see.

The deficit projections are taken from the CBO and OMB and we have converted fiscal into calendar years. A small portion of the deficit financing will come from borrowing from government trust and pension funds, taking a smidgen of pressure off the markets.

We are confident in our estimates of the SOMA Treasury roll-off. The only uncertainty is the final size of the Fed’s post-GFC balance sheet and whether the Treasury maintains a consistent cash balance at the Fed. That is when the Fed will end quantitative tightening.

The combined annual financing needs of the Treasury over the next several years are large and will exceed the GDPs of even some of the largest emerging market economies.

When Fiscal Doves Cry

It surprised us that. the traditional fiscal conservative Republicans, at least in rhetoric, chose to implement a procyclical fiscal policy. Speaker Paul Ryan used to warn the U.S. was the next Greece if it didn’t get its fiscal house in order.

Paul Ryan, Jeff Sessions Warn Obama Budget Could Spur Greek-Style Debt Crisis

“Next year, the United States could be like Greece,” Sessions continued, referring to the severe debt crisis faced by that country as a result of uncontrolled government spending.

Ryan similarly warns on the House Budget Committee website: “The President’s budget ignores the drivers of our debt, bringing America perilously close to a European-style crisis.” – Huffington Post, February 2012

The procyclical tax cuts and spending ramp goosed an already real trending economy, causing growth to accelerate, but it was rare, nonetheless, for the U.S. or any developed economy.

If the larger deficits trigger an adverse market reaction, policymakers may be forced to implement procyclical policies during a downturn. Just as the markets are forcing the EM countries that have been hard hit this year to do — i.e., raising taxes and cutting spending during in an economic slowdown.

Procyclical fiscal policy is puzzling: why would the fiscal authority want to amplify an already volatile business cycle by adding fuel to the fire during booms and aggravating recessions by cutting spending and increasing taxes? – FT

The net result of the higher deficits will be more crowding out in the global financial markets and pressure on long-term interest rates to move significantly higher.

The Diminishing Legacy Of QE

We constructed the following chart to illustrate the schedule of maturing Treasury securities by month, held in the Fed’s September 12th SOMA portfolio.

In the current month of September, for example, $19 billion of Treasury securities mature, but the total falls below the $24 billion monthly quantitative tightening cap (purple line) leaving zero SOMA cash available to reinvest and participate in the Treasury auctions. The $19 billion will not be reinvested and is reflected in the red bar. The Treasury will be forced to plug the gap with new market borrowings or rundown its cash balance at the Fed.

The same dynamics hold for the roll-off of the SOMA MBS portfolio, where the cash balances at the Fed of the government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) are reduced when mortgages run-off and not reinvested.

September To Remember

September will be the first month in several years where the SOMA will not participate in any of the notes, bond, FRN, or TIPs auctions. Recall our early assertion, SOMA’s cash reinvestment of its maturing Treasuries back into the auction does not increase in the public debt.

The same holds for October, when the QT cap steps up to $30 billion per month, as $24 billion of Treasuries mature.

In November, $59 billion of SOMA Treasuries mature, of which $30 billion (the QT cap) will not be rolled over (red bar) and drained from the financial system, with the remaining $29 billion (green bar) in cash used as noncompetitive bids in the variety of notes, bonds, FRN, and TIP auctions.

Some argue SOMA’s impact on the auction and markets is de minis. We disagree.

Asymmetric Effects Of QT

We need to think more about this but our first impression is the economic effect of quantitative easing, and quantitative tightening is not symmetric. Because of the difference on the liability side, QT appears that it will be more direct, more onerous than expected, and will be quicker in its economic impact than QE.

Moreover, QE enabled the government to issue the debt it now has to pay back to the Fed or forced to roll by more issuance of marketable debt.

QE has blurred the lines between fiscal and monetary policy. Quantitative easing (QE) has just been “turbocharged fiscal policy in drag with a lag.” Great hip-hop line, no?

Portfolio Switching

Research at the Fed from last year expected a symmetric decline in demand for risky assets under quantitative tightening relative to QE. The action in emerging markets this year appear to confirm, at least, in part, their analysis.

Carpenter et al. (2015) examined data from the Financial Accounts of the United States and found that the household sector—which in this dataset includes sophisticated investors such as hedge funds—was the predominate seller of Treasury securities to the Federal Reserve during its large-scale asset purchase programs, and that the household sector rebalanced its portfolio toward corporate bonds, commercial paper, and municipal debt and loans. If we lean on their results and apply them in reverse—that is, reverse the actions that were found to occur during that earlier period so as to hypothetically mimic a period of Fed securities redemptions—then we would expect the household sector, as defined in this context, to rebalance its portfolio away from the riskier assets and back towards Treasury securities. – Federal Reserve Board

Reduction In SOMA Treasury Portfolio

The black line in chart above illustrates the decrease in the SOMA Treasury portfolio over time as securities roll-off.

Some argue that the stock of excess reserves are declining too fast, down 18 percent since QT began causing the Fed Funds rate to consistently trade at the top of the 25 bps target range. Consequently, the Fed will be forced to end its balance sheet reduction sooner than the markets think.

A plausible scenario. However, why not just stop paying or further reduce the interest rate on excess reserves (IOER), which will force reserves back into the Fed Funds market putting downward pressure on the rate?

If we had to guess, QT ends in June 2022 when the SOMA Treasury portfolio hits $1.5 trillion and the MBS portfolio around $1 trillion. We suspect, however, the glass will begin shattering long before then, forcing the Fed to reverse course.

…before the financial crisis hit, growth in the Federal Reserve’s securities holdings was in line with growth in nominal GDP. In particular, between 1990 and 2007, the Federal Reserve’s securities holdings totaled a fairly steady share—about 5 percent—of nominal GDP. – Federal Reserve Board

A $2.5 trillion SOMA portfolio in June 2022 would be approximately 10.5 percent of GDP, more than double its holdings before the GFC.

History Of SOMA Participation In Treasury Auction

Our next chart illustrates the SOMA participation in every Treasury auction since September 2009, which was financed by the sum of its maturing securities during each particular month.

The green bars represent the SOMA percentage takedown of the total amount of securities issued during the auctions, and the black line is the corresponding 10-year Treasury yield on the date of each auction.

Operation Twist

The Fed engaged in “Operation Twist” between September 2011 and December 2012 (two red bars) to bring down long-term rates. It sold shorter-term securities in its portfolio to purchase long-term Treasuries. It appears just the anticipation of the program reduced yields as traders began front-running the Fed.

Interest rates began to spike as soon as the SOMA ran out of maturing securities and stopped participating in the auctions. That is what concerns us now.

The SOMA’s participation in auctions going forward will be sporadic, at best, which could put upward pressure on rates and further crowding out borrowers as the Treasury is forced to issue more marketable securities.

The following is the Treasury press release of the results from the August 30-year bond auction. Notice the SOMA took down almost 12 percent of the total outstanding bonds issued.

SOMA Participation Does Not Increase Public Debt Stock

It is important to realize the net stock of Treasury debt does not increase with SOMA participation in the auctions as the cash is derived from maturing securities. Nevertheless, is does allow size of the auctions to increase.

Declining SOMA Auction Participation

Our next chart shows the recent past and future SOMA participation in the Treasury auctions through 2019. The key takeaway here is that the SOMA will be active in the auctions in only five of the next 16 months,

We believe the bond market has not fully focused on the diminishing participation of the SOMA in the auctions going forward. It now has the data and should be on traders’ radar, causing upward pressure on long-term interest rates. We could be wrong in our analysis of how powerful the impact SOMA’s auction participation is on markets, however.

Social Security Now In Deficit

Another significant structural change in 2018 is that Social Security (SS) has moved into structural deficit. In fact, SS began running a primary deficit (noninterest income less payouts) just after the GFC.

Source: Social Security Administration

Our chart below shows the U.S. government ’s off-budget balance, which only includes social security and postal service, the federal entities protected from the normal budget process, and excluded from budget caps, sequestration, and pay-as-you-go requirements. The postal service is a tiny fraction of the balance.

The important takeaway is that the social security surpluses were used to build asset or reserves in their two trust funds:

1) Old-Age Survivors Insurance (OASI) Trust Fund, which pays retirement and survivors benefits, and 2) Disability Insurance (DI) Trust Fund, which pays disability benefits.

If one looks past the cash flow transactions to the impact on actual payments to and from the public, it becomes clear that an increase in trust fund reserves will be associated with a decrease in publicly held Treasury securities. That decrease in turn reduces the Treasury’s current cash needs for interest payments to the public and its need to borrow to make those cash payments.

– Social Security Administration

The large surpluses before the GFC (see above charts) provided a sizeable portion of the financing of the government’s on-budget deficit. For example, the off-budget surpluses from 2002-2008 averaged $173.5 billion per year, which financed, on average, 40 percent of the on-budget deficits.

In other words, social security provided the U.S. government with a significant free-ride of deficit financing, and took substantial pressure off the markets, keeping interest rates low.

The next chart illustrates how the Treasury is becoming increasingly dependent on market financing as the social security surpluses faded and are now in deficit. Marketable debt currently makes up 71 percent of the over $21 trillion total public debt versus 49 percent in 2007.

The upshot? More relative issuance of Treasuries into the market and pressure on interest rates to increase and to crowd out other borrowers.

Globalization

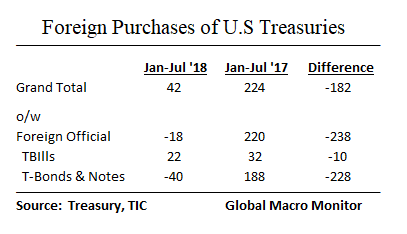

The recent turmoil in emerging markets, which has forced foreign central bank currency intervention to reduce FX volatility, has caused a decline in reserves in many countries, which were held in U.S Treasury securities. The following table shows a -$228 billion swing in central bank notes and bond purchases in Jan-Jul ’18 from the same period in 2017.

The Trump administration’s anti-globalization policies are also having a deleterious effect on capital flows. Adam Posen writes in his Foreign Affairs piece, How Trump Is Repelling Foreign Investment,

U. S. President Donald Trump’s hostility to globalization is ruining the United States’ attractiveness as a place to do business. Sometimes, after all, it takes just one bad landlord to destroy a whole neighborhood’s desirability. This year, net inward investment into the United States by multinational corporations—both foreign and American—has fallen almost to zero, an early indicator of the damage being done by the Trump administration’s trade conflicts and its arbitrary bullying of companies and governments. – Adam Posen, Foreign Affairs

God Forbid Capital Flows Become Weaponized

The following chart illustrates who has funded the U.S. budget deficit, or provided the financing for the federal government’s market borrowing, in this century.

Before the GFC, foreign central banks were providing almost 100 percent of the U.S. government’s borrowing requirements. Former Fed Chairman, Alan Greenspan, lays much of the blame of the credit and housing bubble and Fed’s loss of the yield curve on the issue.

The Fed increased short-term rates from June 2004 to August 2006 by 425 bps, yet the 10-year yield only moved up 36 bps. It’s impotence to move long rates up and cool off the housing bubble eventually resulted in massive imbalances, the eventual collapse of the housing market, and the Great Financial Crisis.

In his Congressional testimony in 2005, Greenspan spoke of this “bond market conundrum,”

..long-term interest rates have trended lower in recent months even as the

Federal Reserve has raised the level of the target federal funds rate by 150

basis points. This development contrasts with most experience, which

suggests that, other things being equal, increasing short-term interest rates are normally accompanied by a rise in longer-term yields. The simple

mathematics of the yield curve governs the relationship between short and

long-term interest rates. Ten-year yields, for example, can be thought

of as an average of ten consecutive one-year forward rates. A rise in the

first-year forward rate, which correlates closely with the federal funds rate, would increase the yield on ten-year U.S. Treasury notes even if the more distant forward rates remain unchanged. — Alan Greenspan, February 2005

The flattening of the yield curve wasn’t a signal but it did significantly contribute to the housing and credit bubble, as foreign central bank demand for Treasury securities caused the Fed to lose control of the yield curve.

Post GFC

The above chart also illustrates the Fed and the rest of the world (ROW), mainly foreign central banks, were the primary financiers of the large U.S. budget deficits after the GFC. Central banks are not price sensitive, and almost all the funding was in the form of QE or printed money, generating practically zero pressure on global financial markets.

That is now changing; the U.S.G is going have to increasingly rely more on the private markets for financing, which do not have unlimited funds and are price sensitive.

Recycling Of Foreign Trade Surpluses Into The Treasury Market

If President Trump is successful in his demand that our trading partners reduce their bilateral trade surpluses, foreign financing of the U.S. budget deficit could dry up causing a “super spike” in interest rates. The administration should be careful what it wishes.

Upshot

More upward pressure on interest rates and crowding out.

There is much hand-wringing, and almost panic in some quarters, about the flattening of the yield curve.

Technical Distortions

Our view is much of stickiness on the long-end of the curve is technical in nature due to distortions caused by QE, substantial foreign central bank ownership of notes and bond, and how the Treasury is concentrating its new issuance in shorter maturities, such as T-bills ($455 billion y/y swing from 2017), and 2 and 3-year notes.

Operation Twist

We were surprised the Fed didn’t unwind Operation Twist when it announced the policy normalization guidelines last year. It was a mistake, we believe, to leave the yield curve so distorted. A well functioning financial system needs a clear market signal from the most important interest rate in the world.

Outlook

The above chart illustrates low-interest rates don’t last forever.

10-year Yield Breaking Upper Trend Channel

This great chart comes to us from Charlie Bilello. We are waiting for the inevitable break above 3.13 percent, which should accelerate the yield move to 4 percent.

Complacency Reigns

The 10-year note volatility index hit an all-time low on September 13th and remains depressed. The record short in Treasury futures is likely a significant factor keeping an underlying bid for notes and keeping yields from spiking in spite of the avalanche of elements moving against the Treasury market. It seems oxymoronic that record shorts are generating complacency.

Inverse Head & Shoulders

We have been watching this inverse head and shoulders, which has been building for almost four years. We expect, at a very minimum, a measured move into the 4.25 to 4.40 percent range, sooner rather than later.

Conclusion

All bets off given a geopolitical shock — we are concerned how quickly U.S.-China relations are moving south; a collapse in stock prices, or a sharp slowdown in economic activity. Haven flows will likely swamp the structural factors pressuring yields higher.

Nevertheless, we have laid out our baseline scenario for yields to move farther and faster than the Street expects, and for the crowding out of the weaker emerging market borrowers to continue.

As always, we reserve the right to be wrong and have attached our usual disclaimer.

Disclaimer

The analysis presented above should be taken as rough, but good, approximations.

Furthermore, we may be entirely wrong in our conclusions.

Abraham Lincoln used to tell a story as a young Illinois circuit court lawyer when trying to convince the jury to render a verdict in his favor.

The story goes that Lawyer Lincoln was worried he had not convinced the jury during the closing argument of a civil case against a railroad. The jurors had gone to lunch to deliberate. Lincoln followed them and interrupted their dessert with a story about a farmer’s son gripped by panic,

“Pa, Pa, the hired man and sis are in the hay mow and she’s lifting up her skirt and he’s letting down his pants and they’re afixin’ to pee on the hay.” “Son, you got your facts absolutely right, but you’re drawing the wrong conclusion.”

The jury ruled in Lincoln’s favor.

Similarly, when looking at data and charts — the facts — we often draw the wrong conclusion about future direction.

Stay tuned.

Almost all of JGB (Japanese bonds) activity comes from the Bank of Japan and Japan’s post office – both of which are required by law to buy JGBs regardless of price. Voluntary purchasers are a tiny tiny fraction of the JGB market. The Nikkei news service often reports about Japanese brokerage house JGB traders napping at their desks and solving sudoku puzzles, with one or two trades happening PER WEEK. Nikkei also reported several weeks in the past year in which there were ZERO trades in JGBs. The proverbial “Mrs Watanabe” is not buying JGBs.

There is no JGB market. Ergo no meaningful inference can be drawn from Japanese 10 year rates. It is a compulsory system where BoJ and the Japanese Post Office seize Japanese savings and use it to facilitate politics.

It is not a coincidence that “Japan Inc” from the 1980s has morphed into “Who Cares?” in the last couple decades. Remember when Sony or Honda or Mitsubishi would sneeze and the entire world stopped in its tracks to check? Remember when market pundits used to give a hoot when/if the Nikkei index was going to revisit its 1989 highs? Does anyone still keep track of the Japanese government’s most recent forecasts of their GDP resuming growth?

This is what happens to a national economy when markets lose confidence in a government.

The USA is losing influence in the middle east, in Asia, in eastern Europe… because every nation knows the USA economy cannot keep up with the federal government’s out of control spending habits.

Massive spending cuts are coming. The $64K question is whether those cuts will be decided by US voters or by US creditors.

Pingback: The gathering storm in Treasury Market – WorldoutofWhack

Pingback: Alea Iacta Est! – Conspiracy News

Pingback: Alea Iacta Est! | peoples trust toronto

Pingback: Alea Iacta Est! | Newzsentinel

Pingback: Alea Iacta Est! | StockTalk Journal

Pingback: Alea Iacta Est! | ValuBit

Pingback: Alea Iacta Est! - Novus Vero

Pingback: Alea Iacta Est! – Wall Street Karma

Pingback: QE’s Fading Legacy Moving Long Yields Higher – Gold Aim Pro

Interesting thesis — but the notion that the US 10-year yield correlates with budget deficits does not square with the historical data. There is zero relationship between the 10-year yield and the budget deficit going back to 1980. What am I missing?

Kg, Its really about how the deficits are funded. For almost 30 years the U.S. G has been able to fund their deficits by central bank and the surplus of the Social Security trust fund. Make sure to read the article in its totality. Thanks for the comment.

Pingback: Social Security In Deficit = More Public Treasury Borrowing – Gold Aim Pro

Pingback: Where The Next Financial Crisis Begins | StockTalk Journal

Pingback: Where The Next Financial Crisis Begins | peoples trust toronto

Pingback: Where The Next Financial Crisis Begins – students loan

Pingback: Where The Next Financial Crisis Begins | ValuBit

Pingback: Where The Next Financial Crisis Begins | Real Patriot News

Pingback: Where The Next Financial Crisis Begins – Conspiracy News

Pingback: Where The Next Financial Crisis Begins | R&L Symmetric Analysis

Pingback: Where The Next Financial Crisis Begins, by Global Macro Monitor | STRAIGHT LINE LOGIC

Pingback: Why The 2018 Stock Market Corrections Are Different – TCNN: The Constitutional News Network

Pingback: Why The 2018 Stock Market Corrections Are Different | peoples trust toronto

Pingback: Why The 2018 Stock Market Corrections Are Different - Novus Vero

Pingback: Why The 2018 Stock Market Corrections Are Different | Newzsentinel

Pingback: Why The 2018 Stock Market Corrections Are Different | ValuBit

Pingback: Why The 2018 Stock Market Corrections Are Different - pustakaforex.com

Why not to devalue the $? Twin deficit will evaporate and America will be great again, I mean US will return to real economy.

Pingback: Mr. Market’s Biggest Headwind | peoples trust toronto

Pingback: Mr. Market's Biggest Headwind - Novus Vero

Pingback: Mr. Market’s Biggest Headwind | Real Patriot News

Pingback: Mr. Market's Biggest Headwind | StockTalk Journal

Pingback: Mr. Market's Biggest Headwind | ValuBit

Pingback: The Dog That Isn’t Barking | My Personal CFO

Pingback: Autopsy On The Still Living Bear Market - NewsBanc

Pingback: Autopsy On The Still Living Bear Market – The Deplorable Patriots

Pingback: Autopsy On The Still Living Bear Market | Real Patriot News

Pingback: THE BATTLE BETWEEN NERVOUS ‘HAVEN FLOWS’ AND ‘BOND BEARS’ – MATASII

Pingback: “Crowding Out” Caused The Q4 Stock Swoon | Global Macro Monitor

Pingback: Thank You, Mr. Gundlach | Global Macro Monitor

Pingback: FOMC: Bid Adieu to QT | Global Macro Monitor

Pingback: Turmoil In The Money Markets & Financing Burgeoning Budget Deficits | Global Macro Monitor

Pingback: It’s Always About The Treasury Flows | Global Macro Monitor